We have entered what scholar Stephen Pyne calls the Pyrocene - a new age where human-influenced fire reshapes our planet. As devastating wildfires tear through Los Angeles, we ask ourselves if this destruction represents our new reality. The events stir strong emotions for our team at Vibrant Planet and Pyrologix. As scientists and foresters who have dedicated our careers to understanding fires and mitigating their damage, we searched within our own systems and data for answers and meaning. Here, we’ve attempted to provide data-driven insights into why the fires happened, and potential solutions for other communities showing similar warning signs.

Understanding the crisis

The extreme fire growth in the Pacific Palisades occurred due to a confluence of factors spanning high winds across fire-promoting terrain, urban planning allowing development in high–risk, hard-to-evacuate areas, and drought-stricken natural vegetation, all of which in combination led to explosive fire conditions. (For a deep dive of risk indicators in the LA area, read the article recently posted by Pyrologix Chief Fire Scientist, Joe Scott.)

The map below overlays critical fire risk zones, indicated by housing-unit exposure, with LA's active fire perimeters as of January 12. Red markings indicate structures facing extreme fire risk, including ember threat, while black lines show current fire boundaries. The devastation is evident – thousands of structures have burned in Pacific Palisades, Altadena, and surrounding areas.

A closer view in the Pacific Palisades:

We calculate housing-unit exposure through a combination of housing-unit density (which promotes house-to-house transmission of fire) and wildfire exposure metrics – including burn probability (will a fire happen?), fire intensity (how will the fire behave if it happens?), and ember load (how far can a fire spread via embers “jumping” away?).

When evaluated together as a series of probabilities of events and fire behaviors that depend on each other (will it burn? If so, how intensely? When burning, will it spread, directly or via ember cast? If so, where?), we can produce a comprehensive measure of a wildfire’s threat to a specific community, and important locations and resources within and adjacent to the community. The next critical question to ask and answer, of course, is what to do about wildfire risks once we understand them.

The layers of wildfire defense

Across many similar communities in the West, wildfire management requires a mix of strategies. A much larger focus must be placed on reducing risk via fuels management in the forests, shrubs, and grasslands surrounding communities with treatments like mowing and hand thinning so suppression resources can safely engage an inevitable fire (in fire-adapted ecosystems, fire is not an if, it’s a when and a how) before it moves into the community. This work is labor- and time-intensive and costly, but absolutely necessary, and can also yield huge co-benefits such as safeguarding water quality, natural carbon stocks, rural livelihoods, and biodiversity.

The other aspect of fuels that can be managed is human infrastructure, including homes, which become fuel for fire if they burn. Managing the infrastructure fuelscape involves land-use and zoning decisions about where to put infrastructure, including homes, as well as hardening of individual structures. Structures must be protected by reducing flammable adjacent vegetation, and hardened with fire resistant building materials, which is expensive, but cheaper to do during the initial build rather than retro-fitting. Multi-faceted strategies can generate multiple layers of resistance, rather than allowing for a single point of failure.

While the Palisades fire is an extreme event that can feel impossible to have prepared for even with the right mix of fuel management and infrastructure hardening, there are still important learnings we can apply elsewhere. Our housing-unit exposure data illuminates pockets of this extreme level of exposure across the LA basin, and indeed all across the Western US. This can be used as a foundational metric for other communities to understand their risk, and prioritize their own mix of vegetation management and home hardening plans.

Which other communities face high wildfire risk?

Pyrologix provides burn probability, fire intensity, and structure risk data for the entire US to wildfirerisk.org. This is a resource for communities to continually understand their local housing-unit exposure, among many other other valuable metrics. Using Pyrologix data, the site maintains a list of states, counties, and communities and their nationally ranked wildfire risk that can be downloaded here. For example, with housing unit and ember load data layered in, Pyrologix maps housing-unit exposure across all of Southern California:

Across the Western US, the data also shows many other communities throughout California’s coast range and Sierra Nevada Foothills, the Colorado Front Range, Utah’s Wasatch front, and in other communities such as Boise ID, Bend OR, Boulder CO, Reno and Las Vegas NV, Santa Fe NM, Jackson WY, Missoula MT….the list goes on across the West – this situation is not uncommon at all, once we all start looking with eyes opened by good risk data.

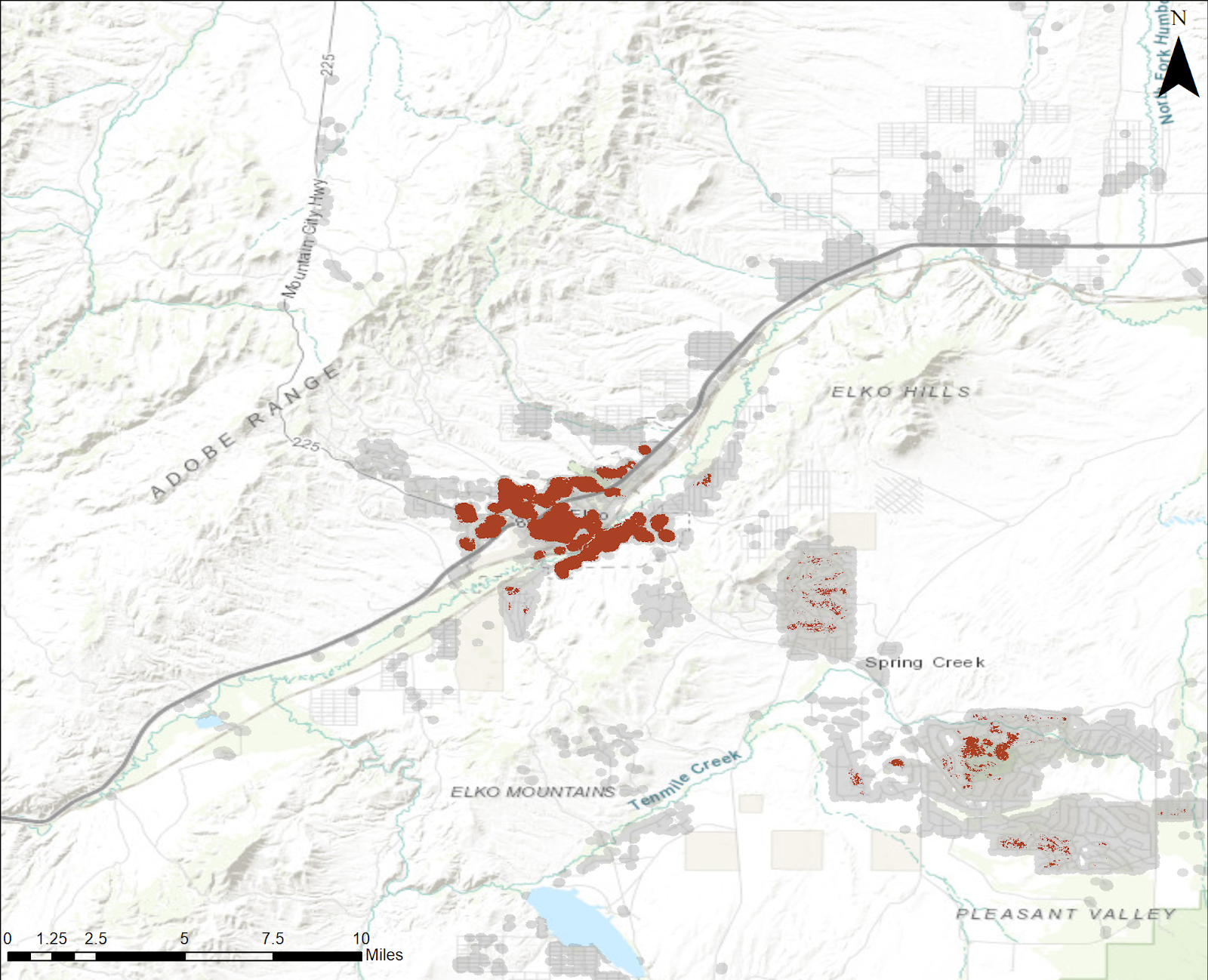

For example, here is housing-unit exposure data for two other communities: Elko, Nevada (near Carlin and Wells), and Alamogoro, New Mexico (Near Cloudcroft and Twin Forks. Red areas represent the top 5% highest level of extreme fire exposure, comparable to that of the Palisades.

Elko, NV:

Ruidoso, NM:

These two examples are representative of what’s true for every other community facing high wildfire risk – each must manage unique landscapes, vegetation types, and even socioeconomic conditions, which will produce different fuelscapes and social enabling conditions and necessitate very different wildfire mitigation strategies. Focused, comprehensive analyses to target effective fuel mitigations and home hardening strategies will be essential for curbing wildfire risk here and across all other communities.

From understanding risk to implementing solutions: how do we stop this from happening again?

- Make best use of risk data to garner public support, funding, and collective action

Dozens of datasets exist to help communities understand their own exposure to wildfire risk, such as burn probability, fire intensity, and structure damage potential. This data tells a powerful story, and can help the many land manager partners involved in planning – including public, private, and tribal ownerships – coalesce around a common picture of risk and mitigation strategies.

- Act urgently to reduce destructive wildfire risk in and around our communities

Wildfire mitigation work needs to happen faster. We need better systems and analytics to understand our landscapes, weather, and assets, and tools to streamline collaborative decision-making across dozens of stakeholders. We need a common operating picture for risk management before an event, just as we have for fire fighting during an event and mitigation of post-fire hazards like debris flow after an event.

We are hopeful that datasets like housing-unit exposure can be used to support more proactive wildfire mitigation project planning. Our goal as an organization is to help communities, states, counties, insurers and utilities understand what’s at risk, and rapidly build efficient strategies with broad stakeholder support to safeguard our communities and ecosystems. But it will take collective action to implement this deeply necessary systems change and maintain, grow and leverage the data and technology that are available to help. We know we can’t change things on our own, nor can we change all parts of the system ourselves. We are leaning into our strengths, and know that others are learning into theirs as well. Let’s lean, and learn, together.